Intermediate Python Tutorial Project Ideas and Tips

Introduction

The purpose of this article is to teach you, the reader, intermediate level Python. I’ll assume you know the basics of Python; you are able to create a quadratic root solver. I will share what my next steps were, as well as how you can follow suit in a shorter period of time by reading 2 years of concepts in this article.

How It All Started

I learned Python basics through CS Circles, and then proceeded to improve/test my problem solving skills. I did this by doing CCC questions which you can find (among other contest problems) at DMOJ. Other sites to improve your algorithmic problem solving skills include HackerRank and LeetCode. Most developers on here are doing it for interview prep rather than broadening their thinking and concepts.

While I was doing this, I was programming with the default IDLE! Four months went by before I learned about PyCharm. Due to redundancy within the IntelliJ ecosystem, I suggest installing IntelliJ IDEA with the Python plugin. This avoids the instllation of more than one IntelliJ products when programming in many languages. IntelliJ has a slight learning curve but is has lots of productivity features. Nowadays, I use both IntelliJ and Visual Studio Code.

I have an entire folder dedicated to snippets of code I could use in the future. I suggest you do the same and you could even add the snippets featured in this article to avoid needless online searching in the future.

General Tips

These are some tips that are not bound to programming but just life and productivity in general.

Know your keyboard shortcuts

Know both the program specific ones (browser, explorer, IDE of choice, etc.) and also OS specific ones (e.g. Win + R for run).

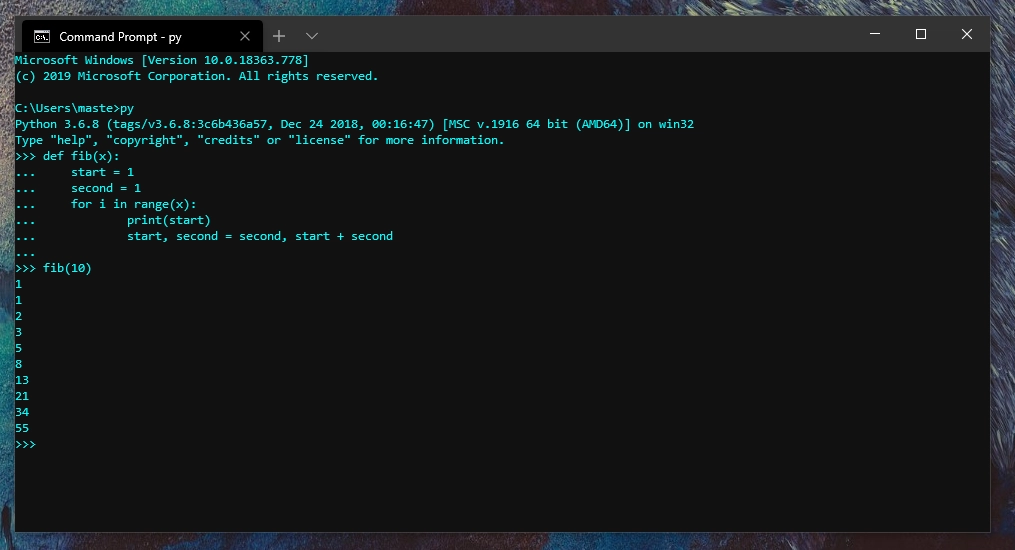

Using the Terminal

Instead of doing a calculation by hand or opening an IDE to create and run a script, you can actually execute Python code from the command line. Aside from the common batch functions (e.g. ls, cd), knowing how to use Python from the command line will save you a lot of time.

How to Search Engine

Google (or your search engine of choice), should be your best friend. It has saved me a lot of time and so it could also save you a lot of time. It can’t do that if you don’t use it or don’t know how to use it. When you Google something, your query needs to be general enough that you can find answers, but also specific enough so that those answers are relevant.

Problem Breakdown Strategy

This goes hand in hand with Googling. Suppose you have a problem/project. You need to break it down into smaller parts. You then need to analyze each of these parts and see if they are small enough for you to complete each of them. If not, either your missing some knowledge that you should Google or the part is too big and needs to be broken down again. You keep doing this recursive procedure until your project has been split into solvable parts so that you can complete them and then weave together a project. When I search and find answers through Google, I don’t expect them to be 100% what I need. I usually need to remix them into what I want and that’s what you should also expect: the bare minimum solution that takes you at least one step forward.

With these tips stated, you can do a couple of different things next. You can skim the rest of the document and make notes on the snippets of code I feature (what I would do personally), read only the headings, skip to the project ideas section, or stop reading altogether as my tips are so useful.

Refresher

In CS Circles, they talk about the print function and some of its optional parameters but it’s easy to forget about them so here they are again.

>>> # The default parameters for print are sep=' ', and end='\n'

>>> print('4', '21', 2020, sep='/', end='\n---------\n')

4/21/2020

---------

Concepts

input() and String Formatting

The input function has an optional parameter so that it can also act as a prompt and if you are using Python 3.6+, you can make use of f-strings.

name = input('Enter your name: ')

print(f'Hello {name}!') # modern way of string formatting

# if input='reader', output: Hello reader!

For Loops

I want to make clear to you that a for loop, is not a while loop as it is in other languages. In Python, a for loop is an iteration over an iterable object.

The range function has three parameters, two of them being optional. The range has a default start value of 0, so unless you need to modify the default step value of 1, supplying a 0 is a redundant.

In this example, I will show you exactly what I mean by “not a while loop” and how a for loop (specifically range) does not add to the temporary value.

# range(start=0, stop, step=1)

# range(5) == range(0, 5) == range(0, 5, 1)

for i in range(5):

print(i)

i += 2

# Guess the output. HINT: i += 2 does not impact the next loop

If you run this code, you’ll notice that the output is increasing by 1 each time even if we are adding 2 to i at the end of every loop. This is because i is set to the next value in range and isn’t a variable being increased by one each loop. This means that we can actually iterate over all sorts of iterable objects, like lists, without having to use range and indexing.

some_letters = ['a', 'b', 'c', 'd', 'e']

for letter in some_letters:

# do something

pass

Here I introduced the keyword pass to avoid the syntax error that come with empty blocks.

If you want to keep track of the index as well as the item, you don’t have to use range, you can use the built-in function enumerate.

# start indicates the start number of the index, not the actual index to start enumeration at!

for i, letter in enumerate(some_letters, start=0):

print(f'item at index {i} is {letter}')

You can think of enumerate as turning an iterable into an iterable of pairs (index, item of iterable at index).

You can also use the next function to retrieve the next value in an iterator (if there is no next item, an error will be raised). All iterators are iterable, but not all iterable objects are iterators! List for example, is iterable but not an iterator so don’t call next on it.

File IO

# make sure there exists a test.txt with content in it

with open('test.txt') as f: # NEW; no close() needed

print(f.read())

# f.read() moves the "cursor" to the end of the file

assert not f.read()

f.seek(0)

assert f.read()

# f.read() returns a string now (unless test.txt is empty)

# ALWAYS SPECIFY ENCODING SINCE WINDOWS & POSIX HAVE DIFFERENT DEFAULT VALUES

with open('test.txt', 'w', encoding='utf-8') as f:

# f.read() ERROR do not do this

f.write('this is a test\n') # note there is no end parameter

f.writelines(['line1\n', 'line2\n']) # note no auto newline

# other modes: a for append, rb for reading-bytes, wb for writing bytes, and r+/w+ for both reading and writing at the same time

# OLD way

f = open('test.txt') # note default is mode='r'

# do something with f here

f.close()

Error Handling

# handling an error

try:

raise RuntimeWarning('Something could go wrong')

except RuntimeWarning as e: # as e is optional

# handle the exception here

# ignoring an error

# old

try:

raise Exception('BOO')

except Exception: pass

# new

from contextlib import suppressdef ignore_error(exception: Exception):

"""

Use three quotes for docstrings or long strings

"""

# use a colon (:) for type hinting (in a dynamic typed language!) and

# yes you can pass exceptions and functions as parameters

with suppress(exception):

raise exception('BOO')

print('not printed')ignore_error(RuntimeError)

print('this gets printed')

By this point if you are following along in IntelliJ, you would have seen some squiggly lines, especially under “Exception” in the above code. These squiggly lines help you to avoid syntax errors, follow style guidelines, and bring attention to code that could be doing something you didn’t want it to be doing.

More Data Types

There are dictionaries, sets and generators (not discussed here). Dictionaries are like hash tables in other languages, because they “hash” the key to store information.

empty_dict = {} # or dict()

my_dict = {'key': 'value'}

# How to get value from dict

my_dict['a'] # raises KeyError if 'a' not in dictionary

my_dict.get('a', DEFAULT_VALUE)

if 'key' in my_dict:

val = my_dict['key']

val = my_dict.get('key', None)

if val is not None: pass

with suppress(KeyError):

val = my_dict['key']

# iterations

for k in my_dict: pass # or for k in my_dict.keys()

for v in my_dict.values(): pass

for k, v in my_dict.items():

# since items() generates the items as the iteration happens,

# my_dict cannot be modified in this loop.

# For modification use tuple(my_dict.items())

pass

# remove key from dict

del my_dict['key'] # can raise KeyError

# if you want to use the value, use .pop() and define a default

# value to avoid KeyErrors

my_dict.pop('key', DEFAULT_VALUE)

# sets

empty_set = set() # {} would initialize an empty dict

my_set = {1, 2, 3}

if 1 in set: pass

# there are many set methods, go check them out yourself

# some include: union, intersect, difference

# you can use + and - as well

Data Structure Usage (Efficiency)

The data structure you use is very important to writing good code.

- use dictionaries if order doesn’t matter + each key has information (value) associated with it

- use sets if order doesn’t matter + no values per key (e.g. keeping track of what you have ‘used’ per se)

- use tuples if you need ordered data but don’t need to modify the data (e.g. coordinates)

- use lists if you need order and mutability (most flexible)

- There are more data structures that are not mentioned in this article. Such as deque, heaps, custom node linked list

You can’t use sets or dictionaries or sets if you need to keep track of duplicates. That’s because sets and dictionaries hash the keys so that it is super fast (O(1)) to check if a key is in a dictionary. This does mean that you can’t use lists, sets, and generators as keys (but you can definitely use tuples as long as lists are not nested).

Dictionaries are also like JSON objects so you can actually use the json module to export them to a JSON file. Note that if you’re using sets as values, they are converted to lists in an exported json file.

Miscellaneous Functions

Sometimes you will see functions like func(*args, **kwargs)

# args = a list of arguments

# kwargs = keyword arguments

# (in the function it'll be a dictionary)

# *args: list in the function **kwargs: dict in the function

def complex_func(*args, **kwargs):

pass

def normal_func(a, b, c, sample_param=5):

pass

sample_args = {'sample_param': 3}

args = [0, 1, 2]

complex_func(1, 2, 3, test='true') # how you'd call it

complex_func(*args, **sample_args) # also works on normal functions

normal_func(*args, **sample_args)

List Comprehension and Ternary

One of the most beautiful parts of Python is list comprehensions; one liners to create lists.

# example: input is space separated integers

integers = [int(x) for x in input.split()]

# split(sep=' ', maxsplit=-1), -1 means no limit

no_negatives = [x for x in integers if x > 0] # only if

positives = [x if x > 0 else -x for x in integers] # if and else

back_to_str = ' '.join((str(x) for x in integers))

# items in the list to join need to be of type str

print(integers)

# this next case demonstrates the ternary operator _ if _ else _

print('list is', 'not empty' if integers else 'empty')

You can also use list comprehensions to create dictionaries and sets

set_example = {x for x in range(3)}

dict_example = {x: x for x in range(3)}

# use generator when only one iteration is required

generator_example = (x for x in range(3))

The third example is a generator. There are some use cases for it, so do your research before using them as they are an advanced topic not for this article.

Iterables vs. Primitives

There is one very important distinction between primitive variables and iterable variables. For example.

a = 5

b = a

a = 6

print(a == b) # false

# vs.

a = [1, 2, 3]

b = a

c = [1, 2, 4]

a[2] = 4

print(a == b == c) # true

print(a is b) # true; same refrence

print(a is c) # false

This is especially important when dealing with nested iterables with how you create nested iterables and also copy them. Try out these examples yourself.

lols = [[0] for i in range(3)] # [0] is created 3 times

lols[0][0] = 5

print(lols) # [[5], [0], [0]]

# vs.

a = [[0]]

lols = a * 3 # same as lols = [[0] * 3]

lols[0][0] = 5

print(lols) # [[5], [5], [5]]

Copying Iterables

To make a shallow copy, use .copy(). BUT, note that for any nested iterables, only the reference is copied, not the actual nested list. That’s why it’s called a shallow copy. To deepcopy, we can use the copy module.

new_copy = lols.copy() # I prefer this over using [:]

reversed_list = lols[::-1]

# I do not use the above since reversed() and .reverse() are explicit

new_copy[0][0] = 6 # lols == [[6], [6], [6]]

assert lols == new_copy and not lols is new_copy

from copy import deepcopynew_copy = deepcopy(list_of_lists)

new_copy = list_of_lists

new_copy[0][0] = 4 # [[4], [4], [4]] because 3x of the same list

assert lols != new_copy and lols is not new_copy

Memoization (Caching)

Memoization is the caching of function return results in order to speed up repetitive calculations. An example would be the recursive implementation of the Fibonacci sequence.

from functools import wrapsdef memo(func): # remove print statements in a practical setting

cache = {}

'''

Without the use of @wraps, square.__name__ would return

'_helper', and the docstring of the original square() would

have been lost.

'''

@wraps(func)

def _helper(x):

# you could have multiple params (x, y, ...) and then

# cache using a tuple as the key

if x not in cache:

print('not in cache')

cache[x] = func(x)

else:

print('in cache')

return cache[x]

return _helper

@memo # square = memo(square) ← what it means

def square(x):

return x * x

for i in range(3):

square(i), square(i) # second one uses the cached result

An exercise is to make a memoize function that takes any number of positional arguments.

Once you understand how memoization works, you can actually start using the built-in version: lru_cache(maxsize=None)

from functools import lru_cache

@lru_cache(maxsize=1)

def get_value():

"""

Calls a function that is resource intensive.

"""

return expensive_function()

Lambdas

Usually used in place of a function parameter if the calculation is short. For example, sorting.

['aa', 'Bb', 'Cc', 'dD'].sort(key=lambda string: string.upper())

[('a', 1), ('b', 0)].sort(key=lambda pair: pair[1])

sorted([('a', 1), ('b', 0)], key=lambda pair: pair[1])

max([('a', 1), ('b', 0)], key=lambda pair: pair[1]) # and min

Modules

Modules play a big part in projects you will do. Some built-in ones are os, shutil, copy, glob, and threading.

For third party modules, you need to use the command pip install module_name in your terminal.

Some common modules are requests, beautifulsoup4, PIL, and flask.

If you’re working on a big project, you’ll probably end up using 3rd party modules. Use a requirements.txt file to track

the modules your project requires. You can install the modules from a file using pip install -r requirements.txt.

os

import os

os.mkdir() # to make a NEW dir

os.chdir() # choose a current working dir

os.getcwd() # get current working dir

os.path.exists()

os.rename()

os.remove() # for existing files only

os.rmdir()

os.getenv('key') # gets an environmental variable# use the shutil module for directories with sub directoriese

Environmental variables

I recommend the python-dotenv module to parse .env files

pip install python-dotenv

# in .env

# KEY=VALUE

from dotenv import load_dotenv

load_dotenv()

glob

Used for getting a list of files/folders

from glob import glob, iglob

# get all .py files in cwd, * is a wildcard

# glob.iglob returns a generator

print([x for x in iglob('*.py')])

# and if you want a list use glob.glob

print(glob('*.py'))

# exercise: find out how to get all .py files in cwd + its subdirs

Threading

Advanced Topics (future Python learning)

Classes

I did not cover classes because that is more about OOP than Python programming and the use cases for classes are very small. One thing you should know when you are learning classes is slots property, so do search that up on your own.

Generators

Again this is an advanced topic and learning about it now will only lead to confusion, its best to learn this on your own or in a practical setting.

Decorators

I covered the basics of decorators. There are decorators used by lots of other 3rd party libraries and different use cases (e.g. timing functions) so I suggest you do your own research on them as well. There is a wraps found in the functools module that’ll help you.

git and git workflow

This is very important when your collaborating with others or are working for a company. Git is a versioning tool used so that mistakes don’t hurt you, and for letting you work on multiple features at the same time.

Other Built-in Modules

Such as itertools, threading, multiprocessing, and more.

Thanks for reading and good luck to your learning journey.