CS 350 Operating Systems

Table of Contents

Concepts

- Operating Systems

- Distributed Systems

- Networking

- Internet of Things

- Computer Architecture

- Embedded Systems

- Database Systems

- Systems and Machine Learning

Course Topics

- Threads & Processes

- Concurrency & Synchronization

- Scheduling

- Virtual Memory

- I/O

- Disks, File systems, Network file systems

- Protection & Security

- Unix referenced as an example

Assignment Helpers

CS 350 CLI

File hierarchy

- cs350 (CWD)

- os161

- userspace

- ASSTUSERX

- cs350_cli.py

How to add to PATH

In your .bashrc, add PATH="$PATH:path". For some reason, my .bashrc file keeps getting wiped.

PATH="$PATH:/u/cs350/sys161/bin:/u/cs350/bin"

Finding stuff in the kernal code

Since you may not have vscode open for the kernel but your entire linux environment, grep may be more efficient.

grep -rnw . -e 'pattern'

This is the command assumes you are in the os161-X.YZ directory.

Setting up on a new Machine

Works even if a custom directory is used for OS/161

# setup new machine

./cs350_cli.py configure

This will copy the sys161.conf file. You will need to edit the CPUs and memory line. I recommend editing one of the commented out lines to have 4 CPUs and 4MB of memory and another one to be 4 CPUs with 2MB of memory.

Building the kernel

# configure new assignment (run once per assignment)

./cs350_cli.py new 1

# build the kernel for an assignment

./cs350_cli.py build 1

If you don’t use the script I wrote, you can do the following read the source code or the course guide and figure out how to build the kernel manually. I’m purposely not providing the commands as I never used them after I wrote my script.

Running the kernel on a simulator

# run the last built? kernel or the one you choose

./cs350_cli.py run [uint]

Debugging

# gdb requires you to run the following in two different terminals

./cs350_cli.py debug 2

# second terminal. The everything before --breakpoints is mandatory

./cs350_cli.py debug attach 2 --breakpoints file.c:30 file2.c:50

In the second terminal, either spam the enter key or enter c to continue code execution as GDB pauses program.

(gdb) c

See Debugging with GDB.

Working locally

To work locally, you will need docker.

Submitting Assignments

# submit and see grade later

./cs350_cli.py submit 0

# internally calls:

# cs350_submit os161/os161-1.99/kern/compile/ASST0 ASST0

# cs350_submit userspace/ASSTUSER0 ASSTUSER0

./cs350_cli.py grade 0

Readelf

You can use readelf to get metadata of a binary

Processes

- A process is an instance of a program running

- Processes can spawn child processes

- Utilizes CPU better (throughput), lower latency

- Simplicity of programming

- Own view of the machine with abstractions

- Programs don’t care which other programs are running

- Pointers are only relevant to one process

Abstractions

- address space

- open files

- virtual CPU

Sections

Programs have sections such as data and text

Creating processes

Posix system calls available in unistd.h

int fork(void);

Creates a new process that is an exact copy of current one. Return process ID (PID) of new process to the parent. Returns 0 in child.

int waitpid(int pid, int *stat, int opt);

wait for process with id pid (-1 for any), set stat to the exit value, and opt is 0 or WNOHANG. Returns PID or -1 on error.

void exit(int status)

Current process ceases to exist. non-zero is error by convention.

int kill(int pid, int sig);

Sends signal sig to process pid. SIGTERM most common value, application can catch it for cleanup. SIGKILL stronger as it always kills the process. HUP stands for hang up or “reload configuration.”

int execve(char *prog, char **argv, char **envp);

prog - absolute path of program run

argv - arguments to pass to main

envp - environment variables

Usually called through wrapper functions. Executes new program. Does not spawn that program. Replaces current program with that program.

int execvp(char *prog, char **argv)

// Searches PATH for prog

int execlp(char *prog, char *arg, ...)l

// List arguments one at a time, finish with NULL

int dup2(int oldfd, int newfd);

// closes newfd if it was a valid descriptor

// makes newfd an exact copy of oldfd

// same offset on both

// stdin is 0, stdout is 1, stderr is 2.

int fcntl(int fd, F_SETFD, int val);

// sets close on exec flag if val = 1, clears if val = 0

// sets file descriptor non-inheritable by new program

perror(char * arg)

Error friendly print

Pipes

int pipe(it fds[2]);

// returns two file descriptors in fds[0] and fds[1]

// writes to fds[1] will be read on fds[0]

// fds[0] returns EOF after last copy of fds[1] closes

// -1 is error, 0 is success

pipesh.c

Use dup2 to read from the pipe[1] and write from the pipe[0] while maintaining the stdout and stdin. stderr is 2.

Implementing Processes

- Process Control Block (PCB) is kept for each process

procin Unix,task_structin Linux,struct threadin OS/161- Tracks state of process

- new and terminated at beginning & end of life

- running

- ready - can run, but kernel has chosen different process to run

- waiting

- Information necessary to run (registers, virtual memory mapping, etc, open files)

- Other data like credentials, signal mask, controlling terminal, priority, accounting stats, debugged, binary emulation, …

Context Switch

- Saving program counter and integer registers (Always)

- Special registers

- Condition codes

- Change virtual address translations

Non-negligible cost

- Save/restore floating point registers expensive

- Flushing TLB (memory translation hardware)

- HW Optimization 1: Don’t flush kernel’s own data from TLB

- HW Optimization 2: use tag to avoid flushing any data

- Cache misses

Threads

- Multi-threaded programs share the address space.

- Typically one kernel thread for every process

POSIX Thread API

// create a new thread identified by thr with optional attributes, run fn with arg

int pthread_create(pthread_t *thr, pthread_attr_t *attr, void *(*fn)(void *), void *arg);

// destroy current thread and return a pointer

void pthread_exit(void *return_value);

// Wait for thread thread to exit and receive the return value

int pthread_join(pthread_t thread, void **return_value);

// tell the OS scheduler to run another thread or process

void pthread_yield();

and more

Limitations of Kernel Threads

- syscalls take 100 cycles, function calls take 2 cycles

- fixed-size stack within kernel

Go Language Routines

- lightweight, 100k go routines is practical

Implementing threads in OS/161

int thread_fork(const char *name, struct proc *proc,

void (*entrypoint)(void *data1, unsigned long data2), void *data1, unsigned long data2)

// wrapper for pthread_create wrapper, does not call process fork

Concurrency

Data races occur without synchronization

Options:

- Atomic instructions: instantaneously modify a value

- Locks: prevent concurrent execution

Sequential Consistency

Execution as if all operations were executed in some sequential order and that the operations of each processor occurred in the order specified by the program.

Requirements for sequential consistency are maintaining program order on individual processors and ensuring writes are atomic.

- Sequential consistency complicates write buffers since CPUs use many caches.

- We want to group writes to the same location (coalescing)

- Complicates non-blocking reads

- Thwarting of compiler optimizations

Does not solve the problem of atomicity since modifying a value is 3 lines of code.

x86 Consistency

Different choice for how to write like (cache, write cache and memory, write to memory only, uncacheable).

x86 Atomicity

lock- prefix to make a memory instruction atomic (locks bus for duration of instruction)- can avoid locking if memory already exclusively cached

- all lock instructions totally ordered

- other memory instructions cannot be re-ordered w. locked ones

- locks are always ordered

xchgcmpxchglfencesfencemfence

Peterson’s Solution

- Assuming sequential consistency

- Assume two threads

int not_turnbool wants[2]

for (;;) {

wants[i] = true;

not_turn = i;

while(wants[1-i] && not_turn == i)

// other thread wants in and not our turn

Critical_section();

wants[i] = false;

Remainder_section();

}

Mutexes

A mutex is a mutual exclusion lock. Thread packages typically provide mutexes:

int pthread_mutex_init(pthread_mutex_t *m, pthread_mutexattr_t attr);

int pthread_mutex_destroy(pthread_mutex_t *m)

int pthread_mutex_lock (pthread_mutex_t *m);

int pthread_mutex_unlock(pthread_mutex_t *m)

// return 0 if successful, otherwise -1 (errno == EBUSY)

int pthread_mutex_trylock (pthread_mutex_t *m);

Only one thread acquires m at a time, others wait. All global data should be protected by a mutex. If mutexes are used properly, then we get behavior equivalent to sequential consistency.

Want to wrap all shared memory writes with a mutex lock and unlock.

// Improved Producer

mutex_t mutex = MUTEX_INITIALIZER;

void producer (void *ignored) {

for (;;) {

item *nextProduced = produce_item ();

mutex_lock (&mutex);

while (count == BUFFER_SIZE) { // remember to do while and not if

mutex_unlock (&mutex); // allow other threads to lock

thread_yield ();

mutex_lock (&mutex);

}

buffer [in] = nextProduced;

in = (in + 1) % BUFFER_SIZE;

count++;

mutex_unlock (&mutex);

}

}

// Improved Consumer

void consumer (void *ignored) {

for (;;) {

mutex_lock (&mutex);

while (count == 0) {

mutex_unlock (&mutex);

thread_yield ();

mutex_lock (&mutex);

}

item *nextConsumed = buffer[out];

out = (out + 1) % BUFFER_SIZE;

count--;

mutex_unlock (&mutex);

consume_item (nextConsumed);

}

}

Condition Variables

Busy-waiting in application is a bad idea, since it consumes CPU. Instead of calling thread_yield, we can sleep until a condition is met.

int pthread_cond_init(pthread_cond_t *, ...);

// unlock's m atomically and re-acquires it upon signal

int pthread_cond_wait(pthread_cond_t *c, pthread_mutex_t *m);

// wake a single thread up

int pthread_cond_signal(pthread_cond_t *c);

// wake all threads up (one at a time though)

int pthread_cond_broadcast(pthread_cond_t *c);

mutex_t mutex = MUTEX_INITIALIZER;

cond_t nonempty = COND_INITIALIZER;

cond_t nonfull = COND_INITIALIZER;

// CV Producer

void producer (void *ignored) {

for (;;) {

item *nextProduced = produce_item ();

mutex_lock(&mutex);

// remember to use WHILE to avoid race conditions

while (count == BUFFER_SIZE)

cond_wait(&nonfull, &mutex);

buffer [in] = nextProduced;

in = (in + 1) % BUFFER_SIZE;

count++;

cond_signal(&nonempty);

mutex_unlock(&mutex);

}

}

// CV Consumer

void consumer (void *ignored) {

for (;;) {

mutex_lock (&mutex);

// remember to use WHILE to avoid race conditions

while (count == 0)

cond_wait (&nonempty, &mutex);

item *nextConsumed = buffer[out];

out = (out + 1) % BUFFER_SIZE;

count--;

cond_signal (&nonfull);

mutex_unlock (&mutex);

consume_item (nextConsumed);

}

}

Use a while loop with these conditions to avoid race conditions of being beat out by another consumer.

Semaphores

- A Semaphore is initialized with an integer N.

sem_waitwill return only N more times thansem_signalcalled- first N calls to

sem_waitdo not block

- first N calls to

Fancy mutex where if n == 0, sem_wait will block.

int sem_init(sem_t *s, ..., unsigned int n); // proc_count_mutex = sem_create("proc_count_mutex",1);

sem_wait(sem_t *s) (originally called P) // P(sem_t *s)

sem_signal(sem_t *s) // V(sem_t *s)

Synchronization

Motivation

Amdahl’s law

- T(1): the time one core takes to complete the task

- B: the fraction of the job that must be serial

- n: number of cores

- Imagine if n was infinity

- Ultimate limit on parallel speedup

- Synchronization increases serial section size

Locking basics

- Lock whenever critical section is required and at least one is writing

Ordering requirements

while (test_and_set (&v->lock))

; // ensure lock is acquired before writing

v->val++;

// this tells the compiler not to reorder

asm volatile ("sfence" ::: "memory");

v->lock = 0;

MIPS Spinlocks

void spinlock_acquire {

...

while(1) {

// first check if the lock is busy to reduce coherence traffic

if (spinlock_data_get(&lk->lk_lock) != 0)

continue; // saves CPU cycles

// attempt to acquire lock

if (spinlock_data_testandset(&lk->lk_lock) != 0)

continue;

break;

}

lk->lk_holder = mycpu;

}

Atomics C11

Portable support for atomics.

To implement mutexes you need atomics. Atomics guarantee something will be written before the next line. (fences). With an Atomic type, all standard ops become sequentially consistent. There’s also a variety of memory ordering from no memory ordering to full sequential consistency.

_Atomic(int) variable_name = 1;

atomic_fetch_add_explicit(&variable_name, 1, memory_order_relaxed);

atomic_fetch_add_explicit(&variable_name, -1, memory_order_relaxed);

atomic_thread_fence(memory_order_release);

atomic_store_explicit(&variable_name, 0, memory_order_relaxed);

int x = atomic_load_explicit(&variable_name);

atomic_thread_fence(memory_order_acquire);

_Atomic(int) packet_count;

void recv_packet(...) {

...

atomic_fetch_add_explicit(&packet_count, 1, memory_order_relaxed);

...

}

struct message msg_buf;

_Atomic(_Bool) msg_ready;

void send(struct message *m) {

msg_buf = *m;

atomic_thread_fence(memory_order_release);

atomic_store_explicit(&msg_ready, 1,

memory_order_relaxed);

}

struct message *recv(void) {

_Bool ready = atomic_load_explicit(&msg_ready,

memory_order_relaxed);

if (!ready)

return NULL;

atomic_thread_fence(memory_order_acquire);

return &msg_buf;

}

Spinlock example. The atomic_flag is a special type without support for loads and store. Implemented lock free.

void spin_lock(atomic_flag *lock) {

while(atomic_flag_test_and_set_explicit(lock, memory_order_acquire)) {}

}

void spin_unlock(atomic_flag *lock) {

atomic_flag_clear_explicit(lock, memory_order_release);

}

Cache Coherence

- coherence means accesses to single memory location

- consistency means ordering between multiple locations

Multicore Caches

Cache = performance but presents an opportunity for cores to disagree about memory. Cache is divided into chunks of bytes called cache lines. Bus or network is used.

3-State Coherence Protocol (MSI)

Cache lines have 3 states

- Modified

- One cache has a copy needs to be written back to memory

- Shared

- At least one cache have a valid copy

- Invalid

- No data

Core and Bus Actions

- Read (load)

- Cacheline enters shared state as data is read without modification intent and could come from cache or memory

- Write (store)

- Invalidates other cache copies

- Cacheline in shared

- Evict

- Writeback contents to memory if not dirty

- Discard if in shared state

Multithreaded Design

Avoid false sharing: avoid placing data used by different threads in the same cache line.

int lock;

char _uused[bytes]; // before C11 / C++ 11 manual padding

alignas(64) struct foo f; // C11 / C++ 11

Avoid contending on cache lines.

Deadlocks

Both threads must lock and unlock in the same order.

lock(a);

lock(b);

unlock(b);

unlock(a);

Solving Deadlocks

- Avoid circular graphs

- Predefine an order in which each lock should be acquired

- You can use the address of the lock to determine locking order

- When there is a circularity, use a system wide lock or a partial ordering

- Can assert locking order statically (VMware ESX)

Wait Channels

// blocks calling thread on wait channel wc

void wchan_sleep(struct wchan *wc);

// wakes all threads sleeping on the wait channel

void wchan_wakeall(struct wchan *wc):

// unblocks one threads sleeping on the wait channel

void wchan_wakeone(struct wchan *wc);

// lock wait channel operations

// prevents a race between sleep and wakeone

void wchan_lock(struct wchan *wc);

// wait

P(struct semaphore *sem) {

spinlock_acquire(&sem->sem_lock);

while (sem->sem_count == 0) {

wchan_lock(sem->sem_wchan);

spinlock_release_(&sem->sem_lock);

wchan_sleep(sem->sem_wchan);

spinlock_acquire(&sem->sem_lock);

}

sem->sem_count--;

spinlock_release(&sem->sem_lock);

}

// signal

V(struct semaphore *sem) {

spinlock_acquire(&sem->sem_lock)

sem->count++;

wchan_wakeone(sem->sem_wchan);

spinlock_release(&sem->sem_lock);

}

Mutex Lock Implementation

struct lock {

struct wchan *wc;

struct spinlock lock;

int state;

}

void lock_acquire(struct lock *l) {

spinlock_acquire(&l->lock);

while(l->state) {

wchan_lock(l->wc);

spinlock_release(l->lock);

wchan_sleep(l->wc);

spinlock_acquire(l->lock);

}

l->state = 1;

spinlock_release(&l->lock);

}

void lock_release(struct lock *l) {

spinlock_acquire(&l->lock);

l->state = 0;

wchan_wakeone(l->wc);

spinlock_release(&l->lock);

}

System Calls

System Calls: Application programmer interface (API) that programmers use to interact with the operating system. They are also a class of exceptions.

Unprivileged code

- Application

- Syscall Library

Privileged

- Kernel

sysctl(): Exposes operating system configuration

ioctl(): Controlling devices

Privilege Modes

- Kernel / Privileged Mode - Operating System

- Access all privileged CPU features

- Setup and mange interrupts

- Controls the system call interface

- Modify the TLB (virtual memory … future lecture)

- User Mode - Applications

- Cannot read/write kernel memory

- Cannot directly call kernel functions

- System library is also kernel memory so library is secure

Mode Transitions

Kernel Mode can only be entered through well defined entry points.

Interrupts

- Generated by external devices needing to signal

- Signal processor through pin or bus message

- Processor executes interrupt handler and preempts running program

- Non-maskable interrupts (NMI) are urgent system requests that cannot be disabled

Exceptions

- Caused by processor. E.g. divide by zero, page faults, CPU errors

- Also called faults

- Program errors: Divide-by-zero, illegal instructions

- Operating System Requests: Page Faults

- Hardware Errors: System check (bad memory or CPU failures)

- CPU stops at instruction that triggered the exception

- Control is transferred to a fixed location where the exception handler is located in privledged mode

MIPS Exception Vectors

interrupt (0), system call (8), or other exception

EX_IRQ 0 /* Interrupt */

EX_MOD 1 /* TLB Modify (write to read-only page) */

EX_TLBL 2 /* TLB miss on load */

EX_TLBS 3 /* TLB miss on store */

EX_ADEL 4 /* Address error on load */

EX_ADES 5 /* Address error on store */

EX_IBE 6 /* Bus error on instruction fetch */

EX_DBE 7 /* Bus error on data load or store */

EX_SYS 8 /* Syscall */

EX_BP 9 /* Breakpoint */

EX_RI 10 /* Illegal instruction */

EX_CPU 11 /* Coprocessor unusable */

EX_OVF 12 /* Arithmetic overflow */

System Call Handling

- EX_SYS (8) exception

- Application loads the arguments into CPU registers

- Load the system call number into register $v0

- Executes syscall instruction to trigger EX_SYS exception

- Kernel processes the system call through the exception handler

- kernel stack

- create trapframe of the program state

- exception type

- type of system call

- run kernel function

- restore state from trapframe

- Returns to userspace using rfe, return from exception instruction

Hardware Handling in MIPS R3000

- Fixed location exception handlers

- 0x8000_0000 User TLB Handler (virtual memory)

- So frequent, handler is hand optimized assembly

- 0x8000_0080 general exception handler

- First 512MB of memory is for the OS

MIPS Coprocessor

- MIPS CP0: system control coprocessor

- System Control Coprocessor (CP0) contains exception handling information

- c0_status

- c0_cause

- c0_epc

- c0_vaddr (fault associated address)

- c0_contex

- MIPS CP1 floating point coprocessor

MIPS Review

- caller-saved registers

- t0-t9: temporary registers

- a0-a3: argument registers

- v0-v1: return values

- s0-s7: callee-saved registers

- jal: jump and link to $ra

- jr $ra: return from function

- registers are saved per-thread stack (stacks are not shared, memories are…)

Application Binary Interface

- System call number in v0

- First four arguments in a0, a1, a2, a3

- Remaining arguments passed on the stack

- Success/fail in a3 and return value/error code in v0

System Call Numbering

Defined in kern/include/kern/syscall.h

Execution Contexts

The environment where functions execute including their arguments, local variables, memory.

- Three types of contexts: Application, kernel, interrupt.

- Context transitions

- Context switch: a transition between contexts

- Thread switch: a transition between threads

Application Stack

Stack made up of frames that contain locals, arguments, and spilled registers. _start frame.

Context Switch User to Kernel

- common_exception saves trapframe of the application context to the kernel stack

- mips_trap decodes the trapframe and the syscall

- syscall decodes arguments and calls sys_write

- syscall stores return value and error into trapframe

- common_exception restores the application context

Preemption

- Can preempt a process when kernel gets control

- Vector controls through system calls and etc.

- Periodic timer

- Device interrupt

- Changing the running process is called context switch

- Processes can vector control to kernel through exceptions and I/O

- Changing the running process is called a context switch

Process Context Switch

- Process Control Block

- Save state into first processes’ PCB

- Reload state from other processes’ PCB

- Save state into other processes’ PCB

- Reload state from first processes’s PCB

Timer Interrupt

- Like before, except EX_IRQ from timer means

- mainbus_interrupt

- timer_interrupt

- thread_yield to pick next thread

- thread_switch to save kernel thread state and restore thread state

- switchframe

Virtual Memory Hardware

Sharing Memory Issues

- Protection

- Bug in one process corrupts memory in another

- Need to also protect against observing other’s memory

- Transparency

- A process shouldn’t require particular physical memory bits

- Resource exhaustion

- Sum of all processors sizes > physical memory

Virtual Memory Goals

- Applications don’t see physical memory, only virutal addresses

- The Memory-Management Unit (hardware) relocates each load

- The MMU is usually patrt of the CPU

- Accessed w. privileged instructions (e.g., load bound reg)

- Translates from virtual to physical addresses

- Gives per-process view of memory called address space

- Prevents one app from messing with another’s memory

- Allows programs to see more memory than exists (relocate memory accesses to disk)

Virtual Memory Advantages

- Can re-locate program while running

- Partially run in memory and on disk

- Idle processes’ memory written to disk so that other processes can read

Load-time Linking

- Linker patches addresses of symbols like printf

- How to enforce protection

- How to move once already in memory (Consider: data pointers)

- What if no contiguous free region fits program?

base + bound register

- Two special privileged registers: base and bound

- When loading/storing,

- Check 0 ≤ virtual address < bound, else trap to kernel

- Physical address = virtual address + base

- To move proces in memory, change base register

- OS must reload base and bound register on context switch

- Need to segment memory to avoid

- expensive process growth

- sharing code/data

Segmentation

Each process has may base/bound regs. Address space is built from many segments. Share/protect memory at segment granularity. Segment is specified in a virtual address.

- Segment table

[Seg] base bounds rw 0 0x4000 0x6ff 10 1 0x0000 0x4ff 11 2 0x3000 0xfff 11 3 00 - Virtual address indicates segment and an offset

- top bits of addr corresponds to 0-index row/segment in segment table, low bits select offset

segment exercises: 0x0240, 0x1108, 0x265c, 0x3002, 0x1600

0x0240 --> 0x4240

0x1108 --> 0x0108

0x265c --> 0x365c

0x3002 --> EXCEPTION

0x1600 --> OUT OF BOUNDS SINCE 0x0600 > 0x04ff

If the segment is invalid (not in table or has invalid rw bits), an exception is thrown.

- Requires translation hardware which could limit performance

- Segments not exactly transparent to program

- Segments need contiguous bytes of physical memory

- Leads to fragmentation

Fragmentation

The inability to use free memory.

External Fragmentation

Free memory between segments that is too small to be used

Internal Fragmentation

Space inside a segment that was allocated for the stack; internal waste.

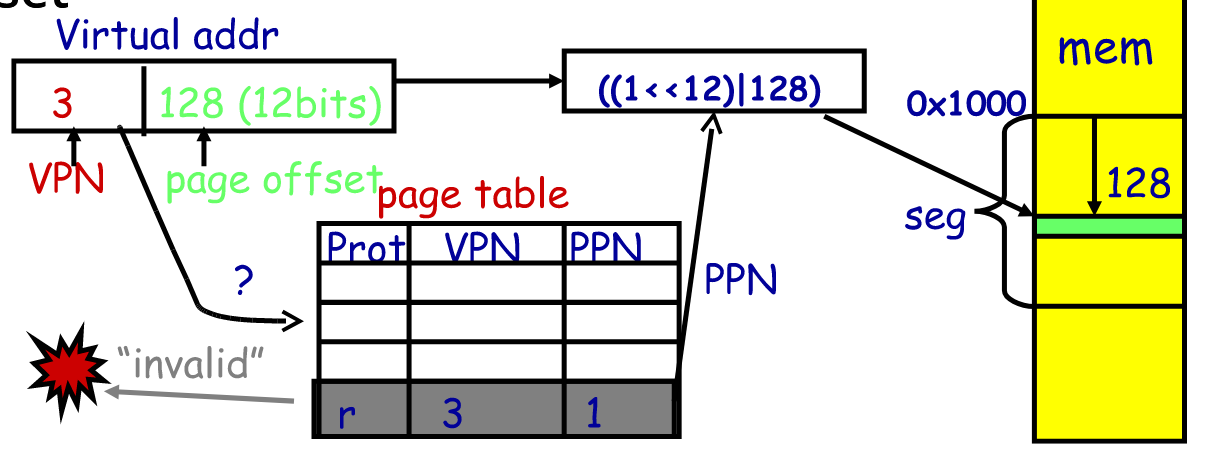

Paging

- Divide memory up into small pages

- Map virtual pages to physical pages. Each process has separate mapping

- Certain operations give control back to OS

- writes to read-only pages

- invalid pages

- OS can change mapping

- Accessed and dirty bits

- Cache control

- Pages eliminates external fragmentation and pages are small enough that average internal fragmentation is .5 pages per “segment”

- Pages have a fixed size. X KB

- log2(X) = bits required for the page offset

- Least significant 12 bits are the offset when page size is 4KB

- Each process has a page table that maps Virtual Page Numbers to Physical Page Numbers

MMUs

Memory Management Units

Hardware Managed MMU

- Hardware reloads TLB with pages from a page tables

- Typically hardware page tables are Radix Trees

- Requires complex hardware

- Examples: x86, ARM64, IBM POWER9+

Intel x86 Paging

- Control registers are priviledged

- bits in a control register (%cr0)

- 4KB pages

- %c43 points to 4KB page directory

- 1024 page directory entries

- physical address of a page table

- page table has 1024 entries

- virtual 4K page per entry

TLB

- x86 CPUs started using translation lookaside buffer (TLB) in caches to speedup page table lookup to avoid 3 memory references per load/store (page directory, page table, physical page access).

- requires flushing on context switch to avoid returning invalid page

- now each entry has a process ID to avoid flushing

OS

- OS lives in same address space of process

- Permission bits

- Map kernel in boot loader

Software Managed MMU

- Simpler hardware and asks software to reload pages

- Requires fast exception handling and optimized software

- Enables more flexibility in the TLB (e.g. variable page sizes)

- TLB fields: Virtual page, Pid, Page frame, NC (no cache), D[irty], V(alid), Global (ignore PID)

- 64 64-bit entries

TLB Instructions

- twlbwr: write a random slot

- tlbwi: write a specific slot

- tlbr: read a specific slot

- tlbp: probe a slot containing an address

Registers needed to be loaded

- c0_entryhi: high bits of TLB entry

- c0_entrylo: low bits of TLB entry

- c0_index: TLB Index

TLB Exceptions

- UTLB Miss: Generated when the accessing useg without matching TLB entry

- TLB Miss: Generated when the accessing kseg2 without matching entry

- TLB Mod: Generated when writing to read-only page

Virtual Memory OS

Increasing Virtual Memory by Paging

The number of pages for a memory system is the size of the memory divided by the size of each page.

To translate a virtual address to a physical address, we replace the starting bits of the virtual address that corresponds to the virtual page number, and replace it with the frame number.

- Use disk to simulate larger virtual than physical mem

- Disk is much slower than memory so find 20% hot to put into memory and 80% cold into disk

- How to resume after a page fault

Restarting Instructions

- Faulting virtual address (In %c0_vaddr reg on MIPS)

- Address of instruction that caused fault (%c0_epc reg)

- Read or write, fetch, user access or kernel access?

- Hardware must allow resuming after a fault

- Idempotent instructions are easy

- A simple load or store instruction can be re-executed

Superpages

- Large mappings

- 2/4 MB mappings

- Sometimes more pages in L2 cache than TLB entries

FIFO Eviction

- Evict oldest fetched page in system

LRU Page replacement

- Worse for looping over memory (better to use MRU eviction then)

- Stamping timer is too expensive as it doubles memory traffic

- Keeping a doubly-linked list is annoying

- Better to approximate

Clock Algorithm

- Do FIFO but skip accessed pages

- Keep pages in circular FIFO list

- Scan all and find a page that isn’t set and Evict

- If A = 1, set A = 0. If A = 0, evict

- Runs when there is very low memory

- When there is larger memory, use two clock hands at a fixed size. The first hands clears and the second hand picks evicted pages

- Can take advantage of hardware dirty bit to prefer clean pages over dirty page. A dirty page has to be written to the disk

Or use n-bit accessed count instead of just A bit. On sweep, count = (A « (n - 1) | (count » 1)). Evict the page with the lowest count.

Random eviction avoids belady and double swaps by hypervisors, and is simple to implement.

Databases are workload specific.

Other Page Replacement Algorithms

- Random eviction

- Used in hypervisors to avoid double swap

- LFU

- MFU

- Specific policies

- Naïve paging: 2 disk I/Os per fault

Page Buffering

Keep pool of free page frames. On fault, evict victim page, and read into free page so that execution can continue while writing out evicted page which is then added to the page pool.

Page Allocation

Thrashing

Threashing is when an application is in a constantly swapping pages in and out preventing the application from making forward progress at any reasonable rate.

Process uses more memory than system has

- working set

- How much cache/memory for process is required

- Only run processes that meet requirements

- page fault frequency

- PFF = page faults / instructions executed

- PFF > threshold = more memory? Swap out if no more memory

- PFF < threshdold = take away memory

Scheduling

CPU Scheduling

Transition States

- new – admit –> ready – scheduler dispatch –> running – exit – I/O or event wait –> waiting

- running – exit –> Terminated

- waiting – I/O or event completion –> ready

Scheduling Decisions

- Switches from running to waiting state

- Switches from running to ready state

- Switches from new/waiting to ready

- Exits

- Non-preemptive schedules use 1 & 4 only

- Preemptive schedulers run at all four points

First Come First Served

If P1 = 24, P2 = 3, P3 = 3,

- Throughput = jobs / total time = 3 / 30 = 0.1 jobs / sec.

- Turnaround time = sum of end times / jobs = (24 + 27 + 30) / 3 = 27

- long periods where no I/O is issued and CPU held

- poor I/O device utilization

Bursts of Computation and I/O

Jobs are both compute and I/O waiting. Therefore overlap I/O and compute from multiple jobs.

Shortest Job First

- Schedule the job whose next CPU burst is the shortest

- Attempts to minimize turnaround time

- Ends up minimizing waiting time and response time

- With preemption, it is called shortest-remaining-time-first

- preemption means if a new job that has shorter CPU burst length, replace the job

- Requires estimating burst time because future cannot be predicted

- Exponentially weighted average

- Tn+1 = alpha * tn + (1 - alpha) * Tn

- Can lead to unfairness and starvation

Round Robin

- Preempts job after some time (quantum) and move it to the back of a FIFO

- Disadvantages

- Context switching

- Saving and restoring registers

- Switching address spaces

- Cache, buffer cache, & TLB misses

- Slower than FCFS

- Context switching

Time Quantum

- 10-100msec

- want larger than context switch cost so that context switching isn’t completely suboptimal

- majority of bursts should be less than quantum, otherwise way too much switching

- not too large that it’s basically FCFS

Priority Scheduling

- Give a CPU to the process with highest priority

- SJF is priority but using CPU burst time

- Starvation - low priority processes may never execute

- Increase a processors priority as it waits

Multilevel Feedback Queue

- Priorities of 0 to 127 and grouped into 32 run queues

- With each queue, run round robin

- Favour interactive jobs

- Run highest priority non-empty queue

Process Priority

- pnice: user-settable weighting factor

- pestcpu: per-process CPU usage

- Incremented whenever timer interrupt found proc. running

- Decayed every second while process runnable

- Load is sampled average of length of run queue plus short-term sleep queue over last minute

- Run queue determined by pusrpri / 4

- For sleeping threads, update pestcpu when runnable using pslptime to avoid unnecessary computes:

Priority Donation

If lower priotity has a lock that medium priority wants, then the lower priority has the same priority as the medium.

If H waits on a lock held by M, then the priotity of M and L both go up, whereas if H waits on just the lock held by L, only L gets a priority bump to H.

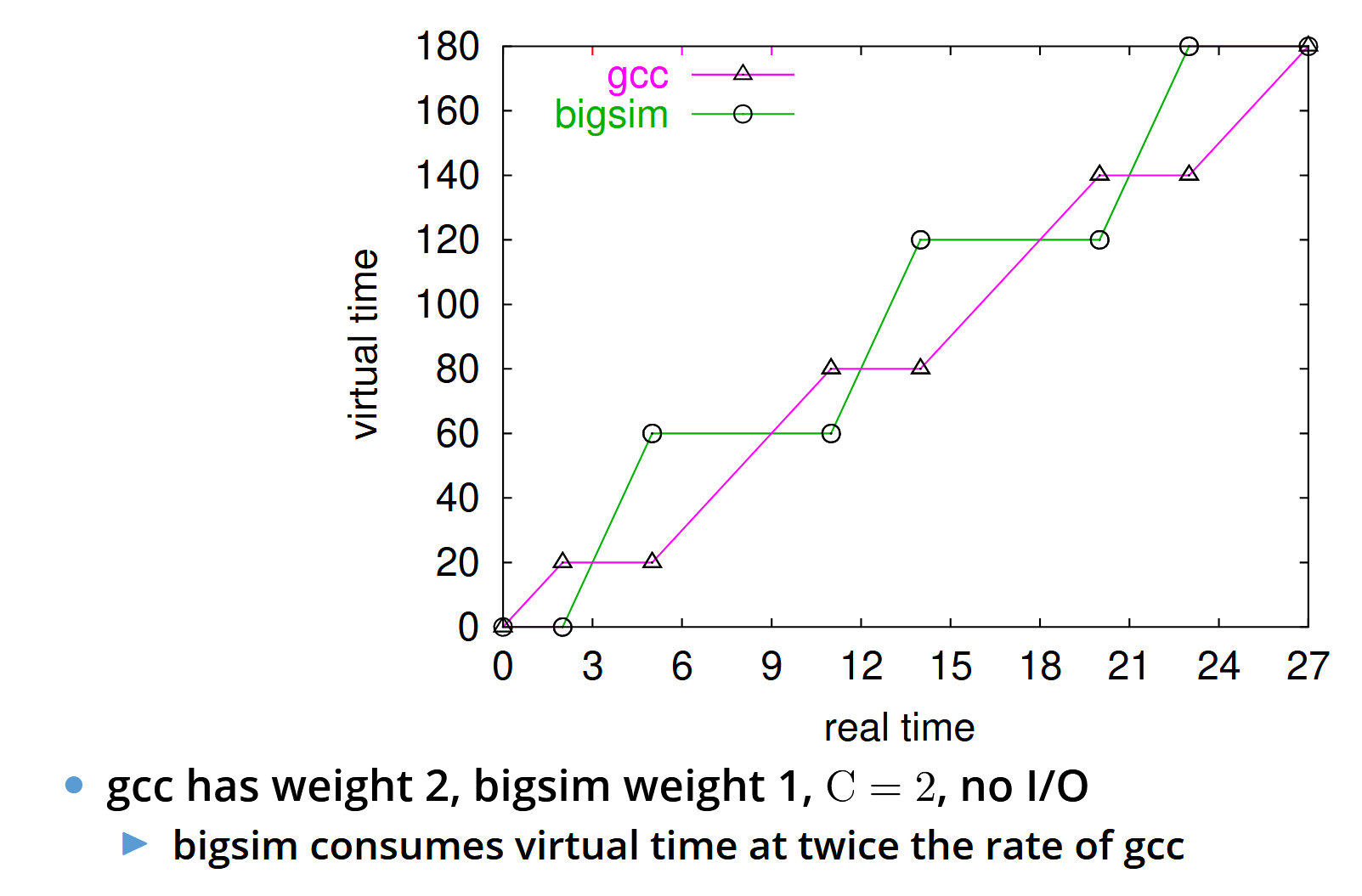

Borrowed Virtual Time Scheduler

- Run process with lowest effective virtual time (E)

- Use weights to get each processes fraction of CPU (seconds per virtual time tick while process has CPU)

- track actual virtual time Ai += t / wi

- Ei = Ai - (warpi ? Wi : 0)

- Wi is warp factor (thread precedence)

- Run j if Ej <= Ei - C / wi

- C is the context switch cost

- Ignore context switch if j has just become runnable to avoid affecting response time

BVT example

Sleep / Wakeup

- Increase actual time after wakeup (decreases priority)

- Otherwise starvation could occur on wakeup

- Scheduler Virtual Time (SVT) is the minimum A for all runnable threads

- When waking up a process, set A to max{A_i, SVT}

- Set A when voluntary sleep and not OS’s doing (network ping is not OS’s doing)

- Processes won’t get more than their fair share by using this method

Real-time Threads

- Some tasks like watching videos, should always be respected when they need CPU, so that’s why a Warp factor exists as shown before

- When process i has warp enabled, then as long as it doesn’t hold CPU for too long (Li), it’s priority for the CPU is boosted when it needs to

I/O

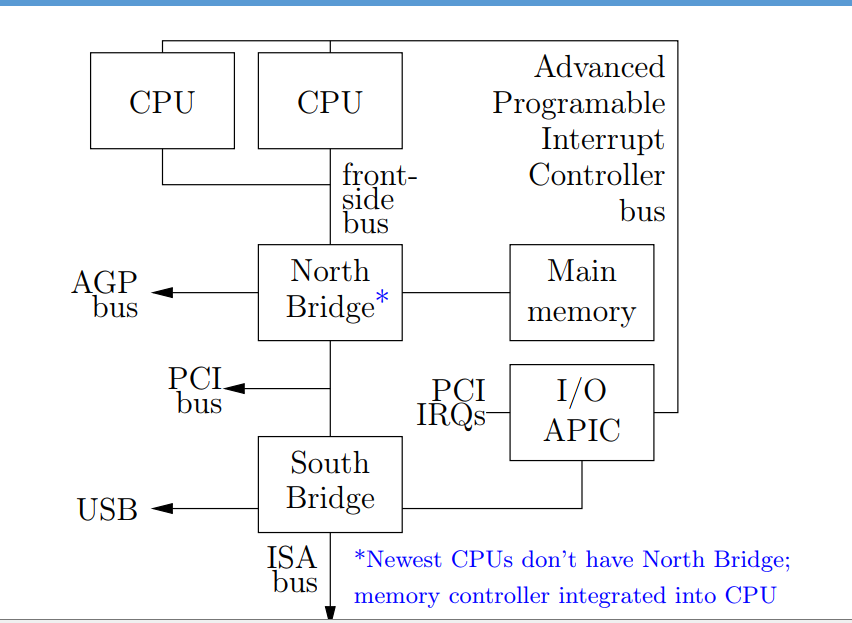

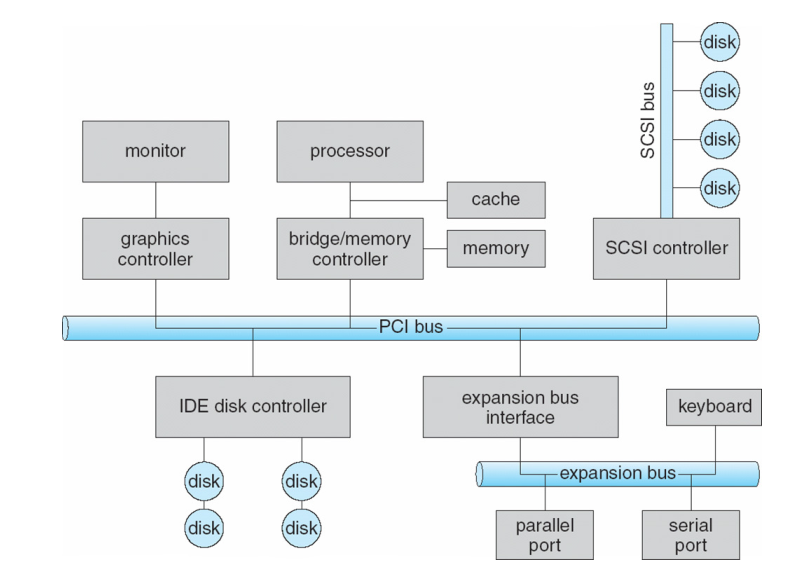

Realistic PC Architecture

I/O Bus PCI Example. Peripheral Component Interconnect Express (PCIe).

Memory and I/O buses

- CPU has a bus to the Memory

- Devices have an I/O bus to the Memory

- Devices can appear to be Memory

Memory Types

RAM stands for Random Access Memory.

- Static RAM (SRAM)

- 4-6 transistors per bit

- very fast, cache slower memory

- two NOT gates

- Dynamic RAM (DRAM)

- 1 transistor per bit

- Capacitor + gate (charge indicates value)

- Slower comparator since charge leaks

- Re-write charge after reading

- Video RAM (VRAM)

- Write and read at the same time (dual ported)

Device Communication

- Memory-mapped devices

- Physical addresses correspond to device registers

- load/store to get status/send instructions

- 216 port numbers

- per-range access control not useful

- OS has to map physical to virtual without caching

- physical address assigned at boot

- Device memory

- OS can write to the device through I/O bus

- Special I/O Instruction

- Some CPUs have special I/O instructions

- OS can allow user with finer granuality than a page

- DMA (direct memory access)

- Overlaps unrelated computation with moving data over I/O bus

- Typically then need to “poke” card by writing to device register

- Keep list of buffer locatioons in memory

- use the CPU only to transfer control, not for data transfer

- Network Interface Card (NIC)

- Bus interface logic uses memory to move packets to and from buffers in main memory

- Steps

- Tell device driver to transfer data to buffer at address X

- Driver tells device controller to transfer bytes to buffer X

- DMA transfer initiated for bytes C until C = 0; memory address increases and C decreases

- DMA interrupts CPU to signal completion

Driver Architecture

- Entry points provided to kernel: Reset, ioctl, output, interrupt, read, write, strategy

- Need to synchronise

- Polling sucks because either CPU is blocked or high latency

- Card should interrupt CPU

- CPU asks card what occured

- High network packet arrival rate can prevent progress = mix of both

void sendbyte(uint8_t byte) {

/* Wait until BSY bit is 1. */

while ((inb (0x379) & 0x80) == 0) delay();

/* Put the byte we wish to send on pins D7-0. */

outb(0x378, byte);

/* Pulse STR (strobe) line to inform the printer

* that a byte is available */

uint8_t ctrlval = inb(0x37a);

outb(0x37a, ctrlval | 0x01);

delay();

outb(0x37a, ctrlval);

}

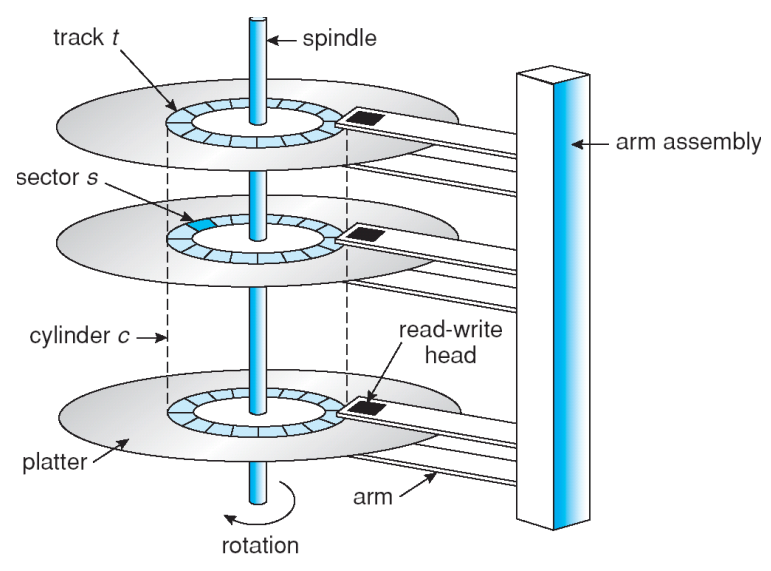

Disks (I/O Subtopic)

- Stack of magnetic platters

- Each platter is divided into concentric tracks and each track has sectors

- A stack of tracks with a fixed raidus is called a cylinder

- Disk arm assembly

- Arms rotate around pivot, all move together

- Arms contain disk heads–one for each cylinder

- Heads read and write data to platters

- One head active at a time

Disk Positioning System

- Move head to specific track

- Keep it there by resisting physical shocks, imperfect tracks, etc.

- Seeking

- speedup - accelerate arm to max speed or hafl way point

- coast - at max speed (for long seeks)

- slowdown - stops arm near destination

- settle - adjusts head to actual desired track

- Settle dominates very short seeks (~1ms)

- Short seeks dominated by speedup (acceleration of 40Gs)

Seeking

- Head adjustments

- Settles take longer for writes because a checksum can be used to retry a read, but a write needs to be perfect otherwise another track got written to

- Disk keeps table of pivot motor power

- Maps seek distance to power and time

- Table set by periodic “thermal recalibration”

- Recalibration hurts audio-video

- Average seek time can be anything from seeking a third of the disk to a third of the time required to seek entire disk

Sectors

- Disk interface presents linear array of sectors

- 512 bytes written atomically

- Disk handles mapping logical sector number to physical sector

- Zoning: puts more sectors on longer tracks

- Track skewing: sector 0 pos. varies by track to speed up sequential access across tracks

- Sparing: flawed sectors remapped elsewhere

- OS assumes disk is blackbox

- Larger logical sector # difference = larger seek

- Can build table to estimate times through emperical tests

Disk Interface

- Controls hardware, mediates access

- Connected to computer by bus that can be contended by multiple devices

- Command queueing

- Disk cache for read-ahead

- Write caching is possible but unstable data

Buses

- SCSI

- Devices: host adapters & SCSI (bus) controllers

- Service Delivery Subsystem connects devices (SCSI bus)

- SCSI-2 bus (SDS) connects up to 8 devices

- Controllers can have > 1 logical units (LUNs)

- Controller built into disk

- Bridge controller can manage multiple devices

- Device is either initiator or target

- Traditionally host adapter was initiator, controller the target

- Controllers can be initiators

- 1 initiaor and at least one target

SCSI Requests

A request is a command from initiator to target

- Commmand

- Target gets control of bus but can disconnect and then reconnect

- Task identifier: initiator ID, target ID, LUN, tag

- Command descriptor block: read 10 blocks at pos. N

- Task attribute: simple ordered, head of queue

- Optional: output/input buffer, sense data

- Status byte: good, check condition, intermediate

- Execution

- Each Logical unit maintains a queue of tasks { dormant, blocked, enabled, ended }

- Simple tasks are dormant until no ordered/head of queue

- Ordered tasks dormant until no HoQ/more recent ordered

- HoQ tasks begin in enabled state

- Initatior can manage tasks

- Abort/terminate, reset

- Linked commands

- Atomic read-modify-write implementation

- Intermediate commands return a status of intermediate

SCSI Exceptions

- Stop executing most commands

- Return “check conditon” status

- Simple device implementation

Disk Performance

- Ordering is huge issue

- Sequential much faster than random

- Power fail leads to inconsistent state

- Order for crashes

- Order requests to minimize seek times

Disk Scheduling

First Come First Serve (FCFS)

- Process disk requests as they come in

- Increases average latency

- Cannot exploit request locality

Shortest Positioning Time First (SPTF)

- Pick requests with shortest seek time

- higher throughput and exploits locality

- starvation (longer seeks never get a chance)

- don’t know which request will be fastest

- Improve with aged SPTF

- Serve lowest priorities, adjust by wait time

- Teffective= Tpos - W * Twait

Elevator Scheduling (SCAN)

- Sweep across disk, servicing all requests passed

- Seeks must be in the same direction

- Switch directions if no further requests

- Bounded waiting

- Biased towards middle cylinders

- Could miss an optimization SPTF would catch

- CSCAN: only sweep in one direction (common in Unix)

- LOOK/CLOOK in textbook

- After reaching disk end, jump to start of disk

VSCAN(r)

- SPTF and SCAN

- Teffective = Tpos + r * Tmax

- 0 <= r <= 1

- r determines how much same direction seeking is rewarded (0 = SPTF, 1 = SCAN)

Flash Memory

- Solid state

- Stores charge

- Charge wears off (Phone off for a year will cause data loss)

- Better heat and power consumption

- Limited overwrites

- Flash Translation Layer to protect physical block = performance impact

- Random write are expensive

NOR flash

- Can execute code in flash itself

- Faster smaller unit reads

- Slower erases

Single-level cell (SLC) vs. Multi-level cell (MLC)

- MLC encodes multiple bits in voltage level

- MLC slower to write than SLC

- MLC is basically more dense at write latency cost

NAND flash

- Higher density

- Faster erase/write

- More errors needing error correction

- 2112-byte pages

- Blocks contain 64 (SLC) or 128 (MLC) pages

- Blocks divided into 2-4 planes

- All planes contend for same package pins

- Block access in parallel

- Limited to reading one page at at ime

- 25 micro seconds

- Must erase whole block before programming

- 2ms

Filesystem

Files: name bytes on disk

- File system: translate name & offset to disk blocks

- Want to reduce number of disk accesses for operations (group related things)

- File system metadata

- An inonde that points to the inode array.

Mappings

- File metadata (inode): map byte offset to disk block address

- Directory: map name to disk address or file #

Intuitions

- perfomance related to disk accesses

- each disk access takes time because of the rotataional delay

Common Patterns

- Sequential

- Processed in sequential order

- Random access

- Access any block in a file without passing predecessors (skipping)

- Keyed access

- Search for block with particular values

DOS FS

- File Allocation Table (FAT)

- Each directory has a mapping of filenames to index in FAT

- FAT contains next block.

- FAT is small enough to be cached is cheaper than disk access.

Indexed files

- requires large chunks of contiguous space space

- array of block pointers per file

- free list for allocations

Multi-level indexed files

- 14 block pointers

- first couple pointer point to blocks

- other pointers point to more and more indirect blocks

Directories

Approach 1: known disk location; {name, inumber}, unique names

Approach 2: Single directory per user

Approach 3: Hierarchical name spaces, graph

Root directory is always inode 2

Special names in FS: (Root: “/”), (Current: “.”), (Parent: “..”)

Special names not in FS: (User dir: “~”), globbing

Use cd to change directory, and ls to list names in current directory

Hard and soft links

- Each inode has a count of hard links

- Use

ln source synonymto create a link - Inode for has special symlink bit set and contains target name (automatically translated by file system)

Fast File System (FFS)

- Original file system

- was slow and required inodes for directories as well

- blocks too smal (512 bytes)

- index too large

- poor clustering of related blobs, inodes far from datablocks, poor enumeration

- lacked atomic file updating

- uses a free list (linked list) of free blocks which gets jumbled and slow to find adjacent blocks

- Cluster related objects together and seperate unrealted items

- With bigger block sizes, split unused large portions into fragments when there is a need to allocate smaller files

- Fixed-size fragments allows the file system to allocate files in a more organized manner, which reduces fragmentation and improve performance

- Uses bit-map of free blocks which is much easier to find contiguous blocks and can be stored in memory, time increases only when fewer free blocks

Clustering in FFS Using Cylinder Groups

- Group at least one consequtive cylinder into a cylinder group

- Order of retrieval is can access any block in a cylinder without a seek, and the next fastest place is an adjacent cylinder

- Put related data in the same cylinder group and unrealted items in another group

- Different directories are placed in different cylinder groups

- Tries to put sequential blocks in adjacent sectors

- Tries to keep same inode in same cylinder as file data

- Tries to keep all inodes for a dir in the same cylinder group

- Each cylinder group is a mini-Unix file system with a starting super block

Bitmap

As said before, a bitmap is used in place of a free list to make it much simpler to find contiguous free blocks. It can also be stored in memory as it is small.

- If a 4GB disk has 4KB blocks, how big is the map? Each bit represents a 4KB blocks, so 4,000,000 KB / 4,000 KB = 1,000 bits = 125 bytes

- Keep 10% reserved without informing user

- Only allow root to allocate from the 10%

FFS Next Steps

- Contiguous blocks are named with a single pointer and length (ext2fs)

- Writes were done synchronously

- Make writes async with write-ordering or logging/journaling

Log-Structured File System

Metadata Synchronously

If we create a directory entry and crash during the middle of creating a directory entry and an IO block, what happens?

- Block on disk

- Inode

- Directory entry pointing to an inode

To ensure things work correctly, we need to flush to disk before the pointer pointing to the inode gets flushed. Therefore, we need to write out the data first, then create the inode, and then create the directory entry pointing to it. When deleting, first delete the directory entry, and then the inode.

Log inode and dir entry to a log first. On crash, re-execute the log to copy back the file system. This is 2x the IO writes. 1GB sized journals.

The Slab Allocator

Object Caching

Allocating an object and destroying it repeatedly is time consuming and wasteful and can be improved upon by using a cache. Use a cached object if it in the cache and upon freeing, return the object to the cache. Better to do this in the central allocator since the OS has more insight into overall memory usage and it avoids bloating the size of the kernel code.

Questions

Question 1 (4)

How does the slab allocator improve the worst-case runtime?

In the worst case, there are lots of objects that are big in size. Objects are cached in the slab allocator meaning that repeatedly allocating and freeing objects will not result in wasteful constructions and destructions. Rather with the cache, the object is simply initialized just once and is retrieved from the cache or put back into the cache. The client can also decide when to create and destroy the cache itself for many objects.

Secondly, this object caching mechanism allows the slab allocator to take up pages for the same object type and use reference counting to free these pages rather than complex data structures that are non-constant in runtime. Therefore, allocations and reclaiming memory is fast as well. When objects are of the same time, they have the same lifetime distribution meaning less chance of pages being held meaning faster memory allocations when there are many applications running and competing for memory.

Question 2 (4)

How does the slab allocator improve the best-case runtime?

In the best case, there are only allocations of small objects at the beginning and frees at the end. The slab layout offers a stub at the end of each slab for containing information about the buffers it has available. The interfaces are extremely lightweight meaning that little memory allocations.

The slab allocator improves the best-case runtime, because as written in 5.3 (2), cache utilization is better. The Slab allocator gives each slab an offset so that buffers are distributed evenly throughout the cache rather than heavily loading the same cache lines. Without the offset, the same lines of the cache would be read since each buffer is of the same object type. The offset alleviates this cache loading and thus improves the miss rate which thus improve runtime even in the best cases.

Question 3 (3)

List the three largest sources of improved OS performance when using a slab allocator?

- Object-cache interface

- Memory management via slabs (no limits, faster counting, same type buffers to reduce fragmentation)

- Slab coloring to improve cache utilization

The Fast File System

512 bytes -> 1024 resulted in 2x performance

- each disk transfer accessed twice the amount of data

- direct blocks contained twice as much data -> most files don’t need indirect blocks Randomization of data blocks causes deteriorated performance due to seeking before access Super-block is at the start of each partition and contains critical data and is replicated.

Question 1 (4)

How does the performance benefits of cylinder groups change with number of cylinder groups? How would you size the cylinder groups on a modern multi-terabyte disk?

The more cylinder groups, the more times the OS can group related data together. This means that bigger files can be stored and be read more efficiently (single pass). For sizing the cylinder groups on a multi-terabyte disk, we can expect files that are many gigabytes in size and so need enough groups to distribute these big files across many groups. We need 10MB cylinder groups to allocate a 100GB file on a 1TB system (1TB / 100GB ~= 10 MB). Reasoning is “The heuristic solution chosen is to redirect block allocation to a different cylinder group when a file exceeds 48 kilobytes, and at every megabyte thereafter.”

Question 2 (4)

One can repair most POSIX file systems through the fsck command. Typically, the computer detects an unclean unmount through the superblock and repairs the file system before the computer starts up by running fsck. If we want to optimize the computer startup time, we need to run fsck in the background and the file system must be ‘correct enough’ to allow the computer to operate on it. Describe at least one precondition all file system writes must adhere to, to allow one to repair the file system in the background after the computer has booted.

Writes must not corrupt the filesystem. For writes to not corrupt the filesystem, at all times, all inodes must point to valid data, and all directory entries must point to valid inodes. Therefore, writes must be done in the order of disk, then inode creation, then directory entry. This ensures that corrupt or random garbage data is not being read or pointed to by a directory entry or inode. This way, fsck can fix any broken pointers in the background while the computer boots fine.

Quesion 3 (2)

If you don’t want to use fragments, how can you reduce the space wasted by very small files (i.e., less than 56 Bytes).

Dedicate end portions of each cylinder group for very small files. So blocks of 56 at the very of end of each group. Then whenever a file needs to be read or written, the OS should try reading from the end of the group rather than the front. Prevent bigger files from writing into these blocks. Since each cylinder group will have a fixed size, the OS should be able to calculate which blocks are of size 4096 and which blocks are of a smaller size, and then prevent writing multiple smaller blocks unless necessary. In essence, dedicated blocks for very small files at the end of each cylinder group where the OS knows beforehand the change in block sizes will enable reducing wasted space without using fragments.